{Snowshill, England}

Ordinary people can sometimes do extraordinary things when given the opportunity and means.

Charles Paget Wade was seven years old when he was sent to live with his grandmother in Great Yarmouth on the coast of England. The heir to a fortune made in the sugar trade, Charles lived a lonely life with his grandmother at Great Yarmouth, with no children close to his own age to help occupy his time. His grandmother’s house was spare and severe, save for one glorious piece of furniture - a grand Cantonese cabinet filled with hidden nooks and crannies and drawers of all sizes and shapes. Charles was allowed to open this cabinet of wonders once a week, on Sundays, and to handle and inspect the family treasures that filled the drawers - but only if he had been well-behaved during the week.

Such was Charles’ fascination with this cabinet and the antique treasures that it held, that when he was old enough to save a little of his pocket money to buy something for himself, he chose to purchase an antique shrine to St. Michael, hand-carved from bone. No toys or candy for Charles Paget Wade!

As he grew older he continued his collecting, picking up historic objects where and when he could find them, and then storing them in the family’s home in Kent. Eventually, upon his grandmother’s death, he inherited the Cantonese cabinet and its small treasures.

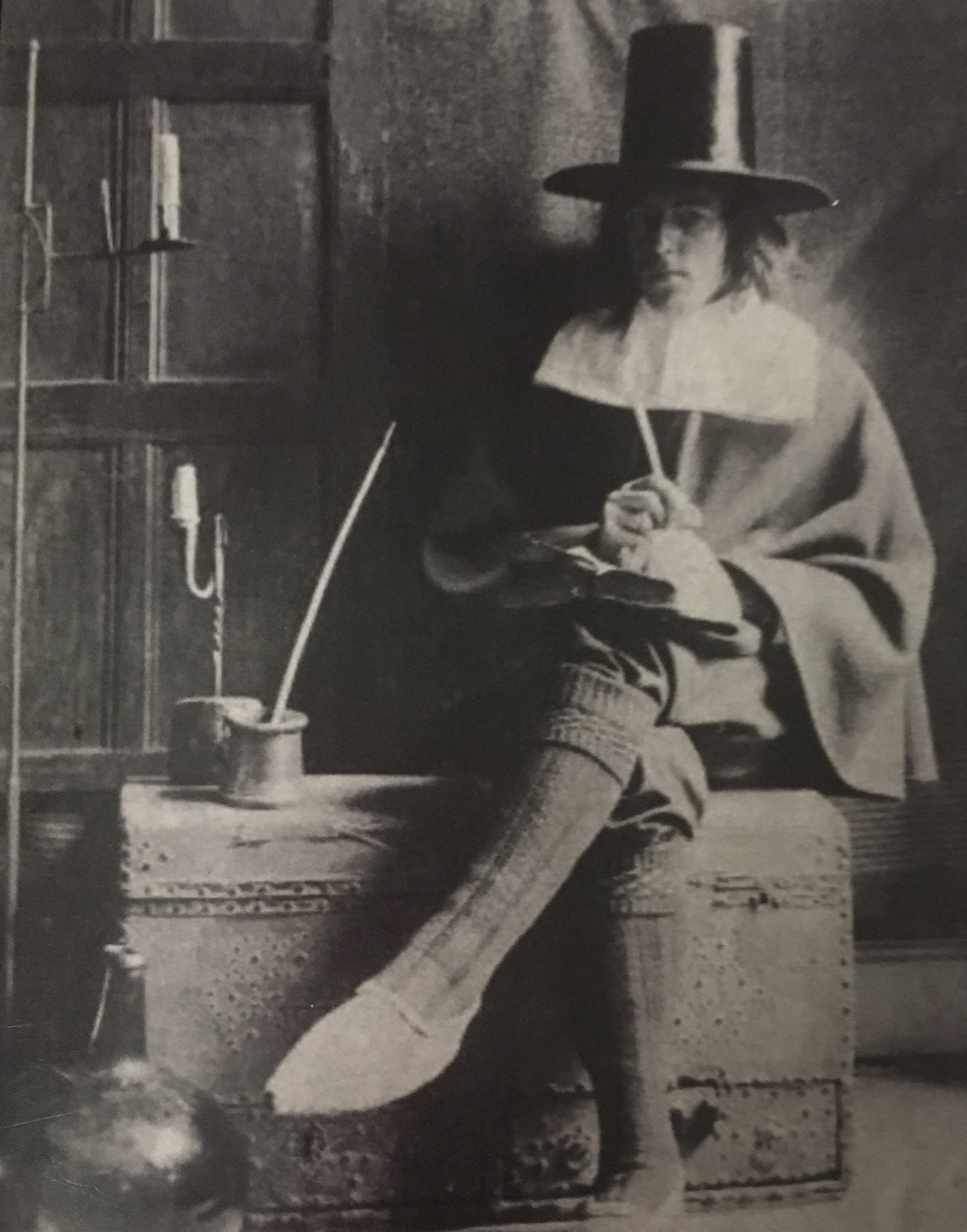

In 1911, a twenty-eight-year-old Charles inherited his father’s portion of the family sugar business. A working architect until that point in his life, he was a young man of many passions: art and architecture, design, theater, and above all, collecting antiques. Suddenly, upon his inheritance, he was a man with not only a fortune but time on his hands. Free from the everyday constraints of a full-time job, he spent the next few years building his collection of objects, while at the same time working part-time illustrating books and pursuing his artistic career.

Wade served in France during World War I, and during his time there he stumbled upon a magazine advertisement for a decrepit old manor house for sale, in the village of Snowshill in the Cotswolds.

He purchased Snowshill Manor in 1919, and spent the next four years renovating first the garden, and then the house. The gardens were designed in Arts and Crafts style with the help of the architect Mackay Hugh Baillie-Scott.

But Charles Paget Wade never lived inside of the manor house at Snowshill. He never meant to. Instead, he lived in a small cottage directly behind the house, with simple plumbing and just a few rooms. Snowshill Manor, it turned out, was purchased to house the vast collection of objects he had been accumulating since he was a child - a collection that eventually numbered almost 22,000 items covering the spectrum of history and craftsmanship.

His collection drew visitors from far and wide, including the Queen of England and many well-known writers and artists. J.B. Priestley wrote about Snowshill in his book English Journey, and described Wade as “one of the last of a famous company, the eccentric English country gentry, the odd and delightful fellows who have lived just as they pleased, who have built follies, held fantastic beliefs, and laid mad wagers.”

When Virginia Woolf visited, she complained that she missed her train upon leaving because - although the house was filled with hundreds of clocks - they were all set to separate times to showcase the individual chimes and bells. No one knew what time it actually was.

The collections at Snowshill Manor fill every corner of every room. They cover the spectrum of antique objects: bicycles, spinning wheels, books, ships, painted signs, suits of armor, masks, pipes, boxes, tapestry, furniture, toys, advertising pieces…and everything else you can imagine. If anything was made by hand, or with an eye for design - CPW wanted to collect it.

He had a weakness, in particular, for the history of costume and clothing. His costume collection numbered almost 2,000 pieces - mostly from the 17th-19th centuries. Some of the pieces are on display at Snowshill, and photographs show that Wade made use of the costumes himself - dressing up for guests as if he were an actor and Snowshill his stage.

In the garden is perhaps one of the most remarkable features of Charles Paget Wade’s collection - a part that he created himself. In 1907 he started work building by hand 1/10 scale buildings and houses that he imagined as a Cornish fishing village. He installed the village around the pond at Snowshill Manor, complete with a working steam train and hand-carved inhabitants, and called the village Wolf’s Cove. It was Wolf’s Cove that drew visitors to Snowshill in the 1930s and 40s - and part of what draws visitors today. The buildings that line the pond these days are replicas - the originals are kept safely inside the Manor, out of harm, and weather’s, way. You can see some of the original buildings above the showcases in the costume room.

When Queen Mary visited Snowshill Manor and Wolf’s Cove, she was left with the impression that Charles Page Wade himself was the most remarkable part of the collection. And when Wade offered Snowshill Manor to the National Trust after his death, the response from the committee was unanimous. The eccentric gentleman had created a property of “exceptional beauty and interest”, and they would be happy to include it in the Trust’s properties.

Charles Paget Wade married a local woman, Mary McEwan Gore Graham, in 1946, and spent much of his time thereafter at a home in the Caribbean. But he traveled back to Snowshill every summer, adding to his remarkable collection until the day he died…

Interesting learning about someone and someplace new!

What a wonderful visit to this remarkable place, through your eyes! You can imagine how we would react to such a collection! Makes our collection of collections look meager! I would love to see the miniature town along the river, with the train and inhabitants. What a creative, imaginative mind. And, money helps!