{Antwerp, Belgium}

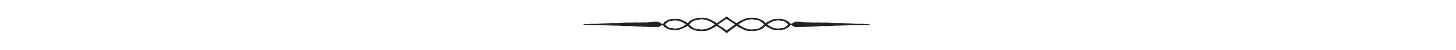

In 1548, a young bookbinder from the Touraine region of France set up shop in Antwerp, Belgium. His name was Christophe Plantin, and by 1555, he had expanded his little bookbinding business to include a print shop, as well.

Book printing was still in its infancy in 1555. Johannes Gutenberg had printed his ground-breaking 42-line Bible exactly 100 years earlier, just a couple of hundred miles away in the German city of Mainz. But it was Antwerp, along with Paris and Venice, that had grown to become a leading center of the new trade.

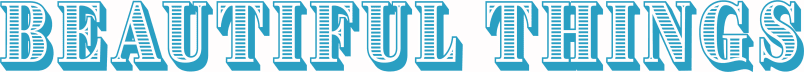

During Christophe’s lifetime, the Plantin Press grew to become the largest and most successful printing house in the world. In 1579, after years of growth and success, Christopher Plantin bought a residence on one of Antwerp’s oldest squares - the Vrijdagmarkt - and moved his press into one wing of the grand building. It remained in business there until 1867, when the press’s building, collection and archives were sold to the city of Antwerp. It opened as a museum and research center the following year.

The Plantin-Moretus Museum is a gem, a little miracle of a museum, really.

The museum suffered damage to one of its wings when a bomb fell on the Vrijdagmarkt during World War II - the museum’s collections had thankfully been packed up and placed in hiding in Brussels - but it was quickly rebuilt. Other than that, very little has changed behind these walls since the 16th century, and you can feel it.

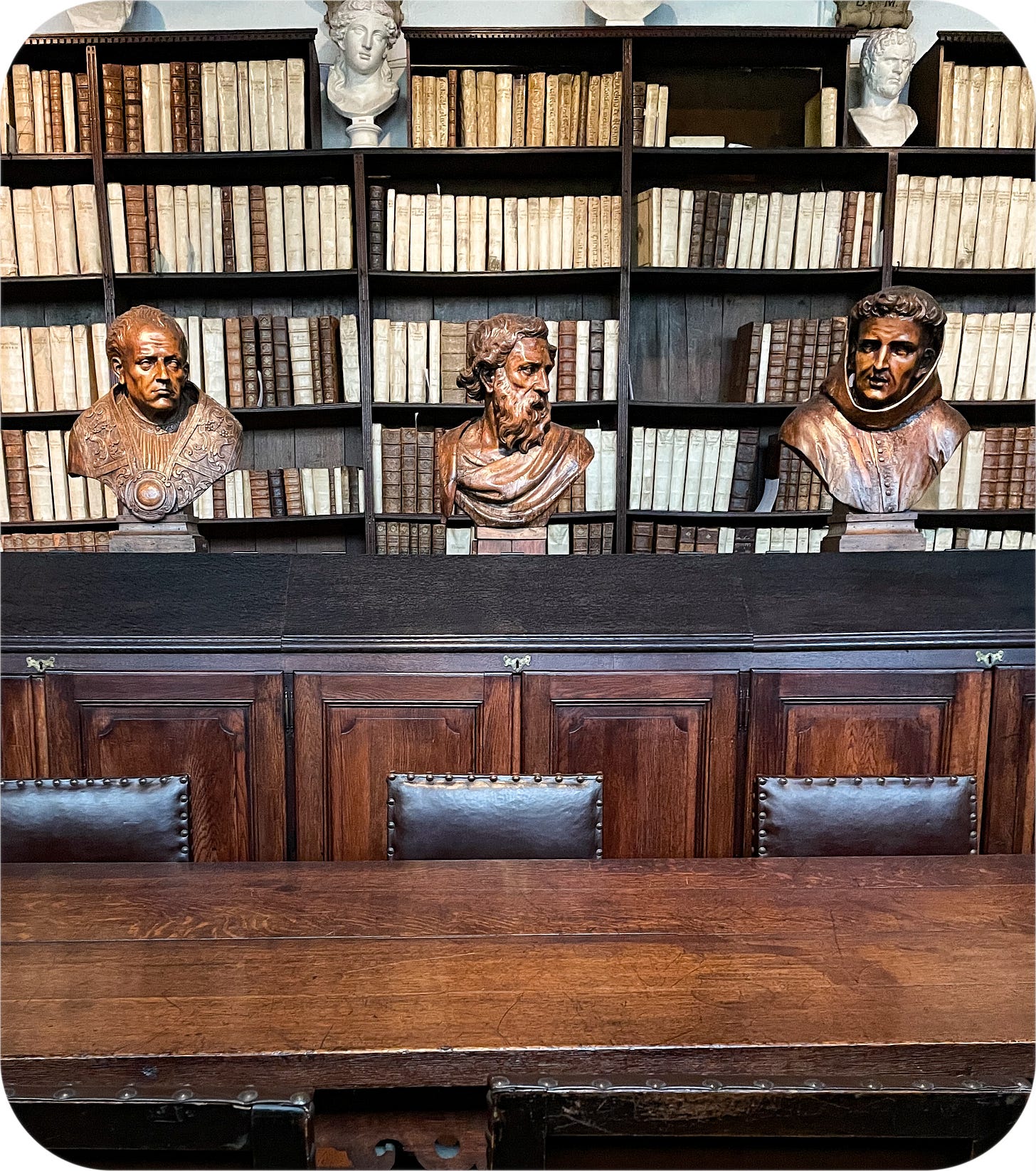

It’s easy to be awed by the press’s library, lined with books bound in deep-aged leather and ivory vellum…or the printing room, home to eight original printing presses - including the two oldest existing presses in the world. (Watched over by the Virgin Mary, like so much of Antwerp - remember, she keeps the giant Lange Wapper at bay.)

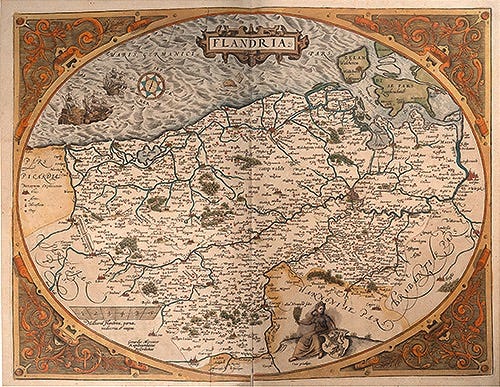

Or the museum’s collections, which include works by fellow Antwerpian Peter Paul Rubens (who designed frontispieces for Plantin, and painted portraits of members of the family), and a copy of the world’s first atlas: Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, first published and printed by Plantin in 1570. Ortelius was born in Antwerp, and worked as an illustrator for the Plantin Press while preparing his maps for publication.

But it’s the more intimate areas that fascinate me, like the foundry where the press’s type was cast, or the little store-front in the corner where the public could stop by, buy a book (loose-leaf, as they were sold in the 16th century), or order a binding by the press’s bookbinders.

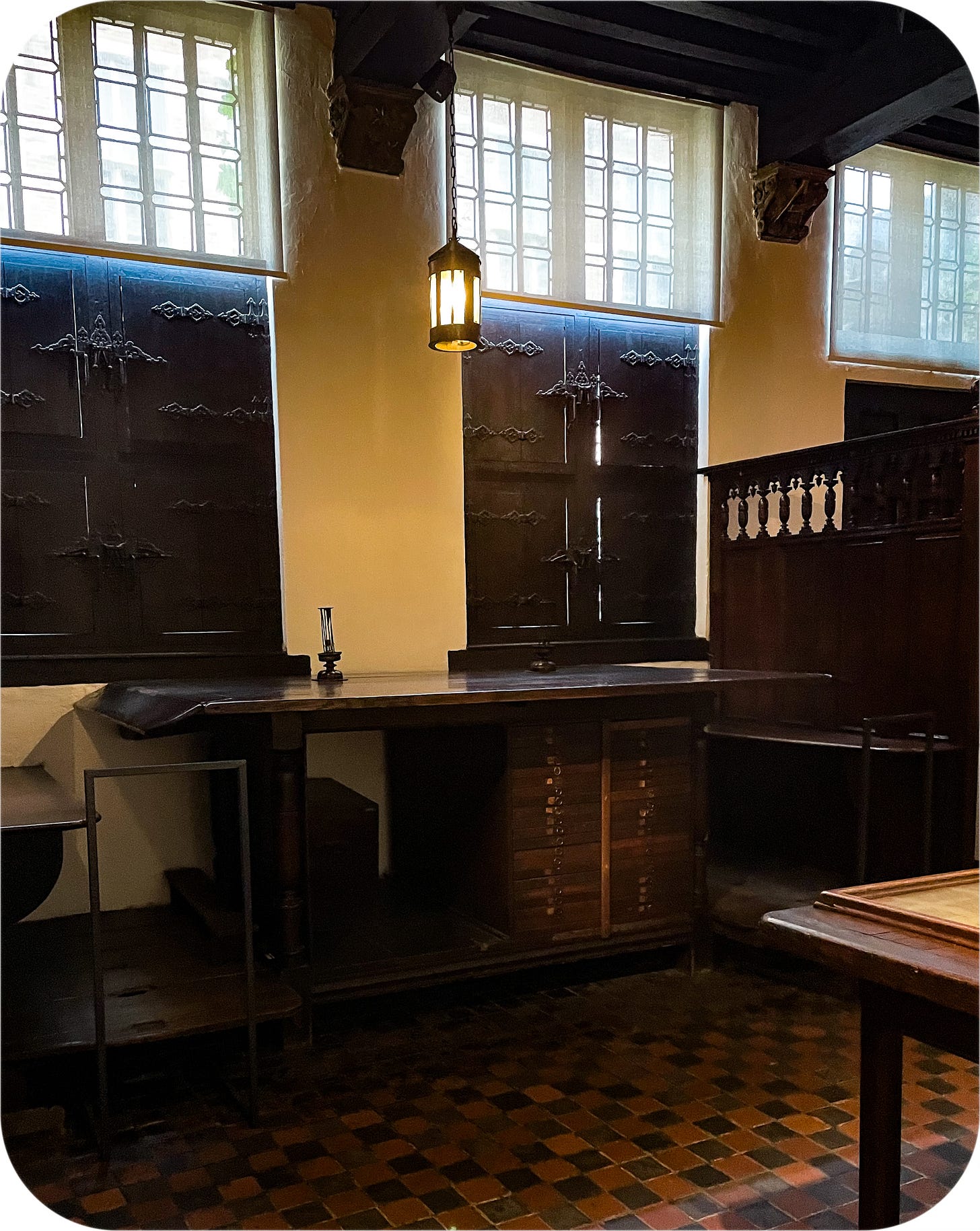

Or the proofreader’s desk: a built-in table, really, situated next to large, shuttered windows that helped to illuminate the proofreader’s painstaking work.

Christophe Plantin was so proud of his operation - and his proofreaders - that he would post proofs of his works on the exterior walls of the press, and offer a reward to anyone who could find a mistake.

Antwerp was part of the Spanish Netherlands in the late 16th century, and as such was ruled by the Catholic King Phillip II of Spain. In the early 1660s, Christophe Plantin was accused of heresy after a raid on his press turned up a Calvinist pamphlet. Plantin fled to Paris, where he stayed for two years until his name was cleared.

(Plantin was in fact a Calvinist sympathizer, although he himself was a member of the Familia Caritatis - “Family of Love” - a quiet, mystical sect founded by Henry Nicholis in Germany. The Familia Caritatis helped to fund the Plantin Press.)

During his exile, his business’s furnishings were sold on the Vrijdagmarkt, where a flea market and auction had been held every Friday since the 12th-century. (You can still attend auctions on the Vrijdagmarkt every Friday!) Plantin’s Calvinist friends purchased all of his business equipment and, when Plantin returned to Antwerp, they became his business partners.

While Plantin continued to publish “heretical” works on the down low, it was important to him to win the favor of King Phillip II. He began work on a polyglot Bible, printed in five languages: Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic and Syriac. The project was monumental: the Bible was printed in 11 volumes, and required new sets of type in Hebrew, Greek, and Syriac. Plantin bought additional printing presses and hired forty extra printers. King Phillip promised funding for the project, and sent a Spanish theologist to supervise the project.

1200 copies of the Bible were printed on paper, and 13 were printed specially on vellum for the King himself: the printing took six years. The result is considered not only the masterpiece of the Plantin Press, but one of the great masterpieces of Renaissance printing. Very few copies exist today - many of the paper copies were lost in a shipwreck in 1572. (There is a full copy on display at the Plantin-Moretus Museum. Copies very rarely come up for auction, but if you’re interested, it will cost you.)

King Phillip II, presumably pleased with the result, appointed Christophe Plantin “Arch-Printer to the King”. He was given contracts to print liturgical materials for the Catholic church in Spain and all over Europe. Eventually Plantin - member of Familia Caritatis and Protestant sympathizer - became the greatest publisher of Counter-Reformation printed material of the Renaissance.

Christophe Plantin died in 1589, leaving his printing house to his son-in-law Jan Moretus, who had been been a longtime apprentice and collaborator of the press. When Jan Moretus died in 1610, his widow Martina Plantin became the head of the family business. As a consequence of Martina’s success, over the next two hundred and fifty years, Moretus women would manage the company for extended periods of time, and - according to the museum’s website - it was the management of these “strong, emancipated women” that guaranteed the company’s prosperity and longevity.

PS - As I write this, it occurs to me that not everyone might be as excited by the idea of visiting a 16th-century printing house as I was, but I am here to tell you that the Plantin-Moretus Museum is truly a magical place. If you are interested in books, or printing - the history of books, or the history of printing, or history in general, or time-travel, or if you have a curiosity about the past in any way, shape or form, please do yourself a favor and visit if you ever find yourself in Antwerp.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider becoming a subscriber to have Beautiful Things delivered to your inbox. Subscriptions are free unless you choose otherwise. If you are interested in reading my previous letters from abroad, visit my homepage at: Beautiful Things. And please remember to heart, comment and share to your heart’s content - it helps others discover my little corner of the world. Thank you for reading!

I’m so happy to see someone who adored this museum as much as I did! Everything about it is a historian’s dream, I felt like I was just floating through it. And I had no idea of the religious dynamics of Plantin’s life - how impressive that he went from being religious exile to a favored printer of the Spanish king. Thank you so much for sharing!

Fascinating. I might be going to Belgium this coming autumn or in 2026, so I'll keep this place in mind.