{Siena, Italy}

Regular readers of my letters will know that I like the travel writing of Henry James very much. Part of it, I think, is the idealized version of travel at the end of the 19th century that he portrays. Our friend Henry is always traveling by carriage, arriving in unfamiliar cities by moonlight, and sitting down to warm suppers in cozy inns. Although the reality was likely less romantic than it seems, it’s hard not to be drawn in, for example, by his arrival in the Tuscan city of Siena. He writes:

“I arrived late in the evening, by the light of a magnificent moon…”

Of course he did. After checking into his cozy inn, James walks to the heart of the city, the wedge-shaped Piazza del Campo, which, he writes, “…was void of any human presence that could figure to me the current year; so that, the moonshine assisting, I had half-an-hour’s infinite vision of medieval Italy.”

In Siena, for once, art imitates life. My first view of the Piazza del Campo is by the moon's light one chilly November evening. And even though the white utility van that seems to follow me around Europe, parking anywhere that I’d like to take a picture is right there front and center before the grand Palazzo Pubblico - it’s still easy to get lost in a Medieval reverie.

Construction began on the Palazzo Pubblico in 1297, at the height of Siena’s power as a city-state. Its most striking feature is the tower at one end, the tower that Henry James wrote “soars and soars till it has given notice of the city’s greatness over the blue mountains that mark the horizon.”

Siena lies in the heart of Tuscany, just about fifty miles south of Florence. It is built over a series of hilltops so that you can visit a park at one end of the city and look down into a valley and back up to the glorious cathedral that sits at the city’s highest point on the adjacent hill.

The few commercial blocks surrounding the Palazzo Pubblico are bright, and filled with shops and people, but duck through an alley or a passageway, and you’ll find yourself walking through narrower, winding streets, with dark cobblestones below your feet and laundry drying and blowing in the wind above your head.

Being so close to the palazzo I get used to quite a bit of noise at all hours of the day, but one night soon after my arrival I’m awakened just past midnight by a loud commotion nearby. Drumming, it sounds like. And singing.

If it were just singing I would assume it was simply young people heading home after a night of drinking - but the drumming has me up and peering through the dark window. It’s just one drummer and a large group of people, some of them carrying flags. This is my introduction to the contradas of Siena.

The contradas (contrade, in Italian) of Siena are, technically speaking, neighborhoods: seventeen of them. They are neighborhoods, though, with very strict boundaries. Each contrada has a name, and a mascot, and a flag… and its own church and fountain. They were developed in the middle ages, and are taken very seriously to this day. You are a member of the contrada where you are born, regardless of where your parents live, or if you move. Babies can become members of their parents’ contradas if they are baptized in the fountain that represents that particular district. From what I understand, Sienese babies are baptized twice - once in the church, and once in the contrada’s fountain.

Contradas have meetings and parties - and it seems they can get pretty animated because it was one of these gatherings that I witnessed on the palazzo early that morning.

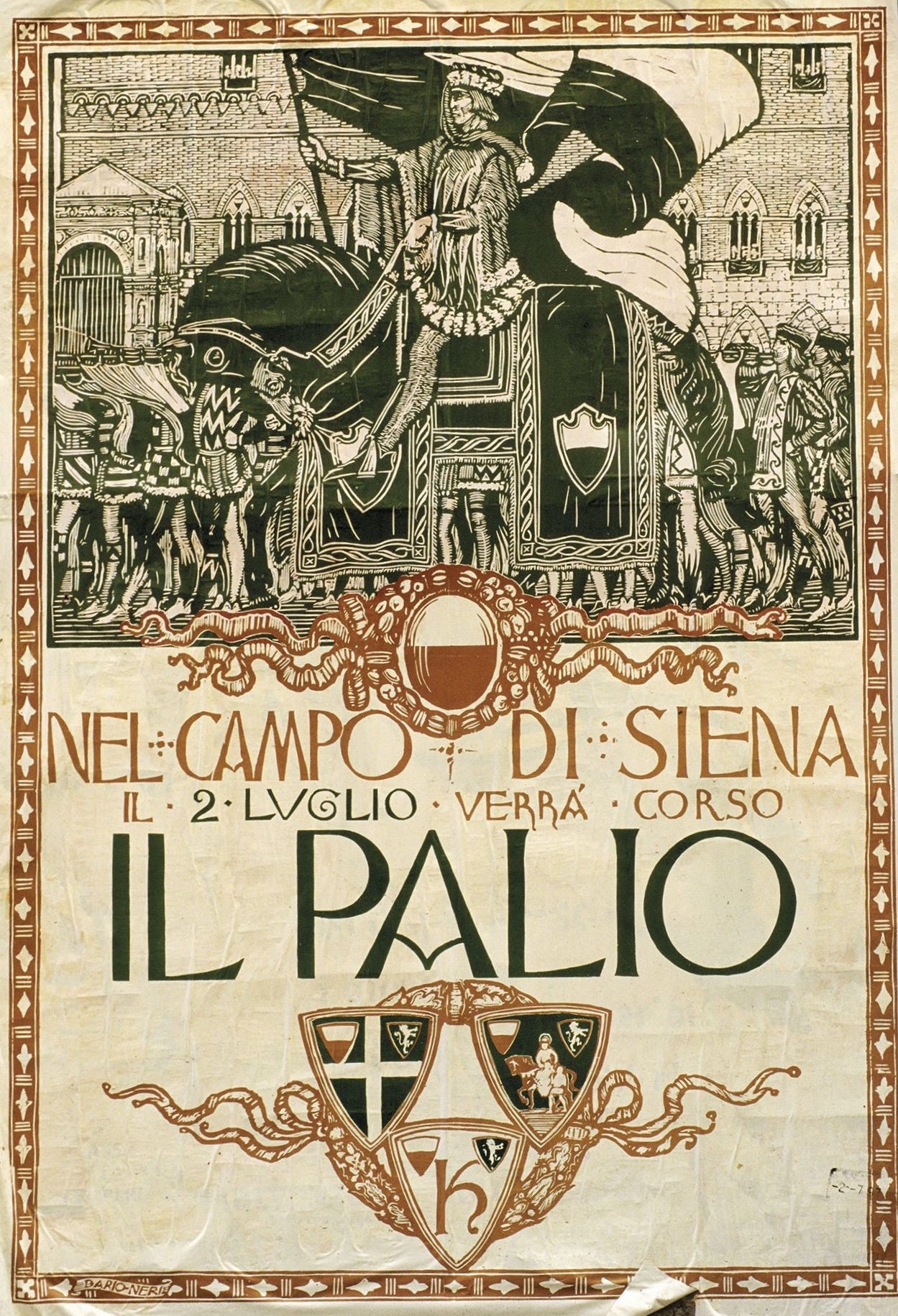

Twice a year, Siena’s most famous event, the Palio di Siena, occurs on Piazza del Campo. Amazingly - considering the piazza’s size - it is a horse race, and the ten horses that run in each of the races represent ten of the city’s contradas.

(The participants are chosen at random, in case you were worried - each contrada participates in at least one Palio each year.)

The races have been held for centuries, each year on July 2nd and August 16th. Up to 30,000 people cram into the piazza on race day - filling every inch of the infield, every balcony window and rooftop.

I’m sorry not to be in Siena for the Palio, because it sounds amazing. The traditions make me laugh when I read about them: the horses cannot be purebred, they must be mixed-breeds. The jockeys dress in Medieval uniforms and not only is bribery allowed, it is encouraged.

Of course, at the end of the day, despite the ceremony and celebration, the city takes the horses’ safety very seriously. Safeguards are in place to prevent injury, and the conquering horses are treated like the reigning heroes that they are.

It’s getting late in the year, and local shops are filled with panettone, pan d’oro - the airy, golden, star-shaped treat that is half bread/half cake - and Sienese specialties like dense panforte and ricciarelli, an almond cookie similar to amaretti. I’m not crazy about panforte, but since I’ve arrived in Siena I’ve been eating ricciarelli like it’s my job. It’s as if someone has asked me to locate the best ricciarelli in Siena and I’m on a mission to find them. (No one has asked.)

I’m not wild about the super-chewy variety at the bakery the internet tells me is the best in town, but I do fall in love with the ricciarelli at Nannini, a cafe near the center of town that is a Siena institution. It is my favorite place in town, mostly because after a few days I understand exactly how to order…but also because they have the most delicious breakfast thing: two pieces of bread that are caramelized and I think filled with marzipan or some type of almond cream. I like it so much, that when I return from Italy, I post a query on Substack notes, to see if anyone knows exactly what that thing was. The results were inconclusive, but I would still like to know - so if you find yourself at Nannini in Siena, check for me, please.

{Cortona}

Tuscany is known for its hill towns, and possibly no town is hillier than Cortona. Or at least it feels that way as I climb the very, very steep and endless route up to the Basilica of Santa Margherita of Cortona. The basilica is, of course, perched at the very highest point in town, and on this rare sunny day in November it is a long, hot walk.

I was warned. On my arrival in town I had struck up a conversation with a very nice couple from New York who were staying in Cortona for a month. They were kind enough to show me around the small town center, and as they said goodbye they pointed to a street off the main square and said “The basilica is that way. It’s a long walk and you may not think it’s worth it. You might not want to go…”

Of course I want to go!!

Forty-five minutes of climbing later, I’m not so sure. The basilica is beautiful, admittedly, with a striking blue-frescoed ceiling adorned with golden stars.

But it’s the lighted case near the altar that startles me.

I’ve spent several months in Italy over the past couple of years, and I’ve grown accustomed to religious relics. There was the tongue of St. Anthony in Padua, and on display back in Siena is the severed head of St. Catherine of Siena. Catherine’s head was separated from her body in Rome and smuggled back to Siena - legend has it that the head was temporarily transformed into a basket full of rose petals along the way to her home in Siena, to escape the guards who were meant to protect her.

But, although I am used to relics, I’m not prepared for the glass case in Cortona’s basilica that holds the entire incorrupt body of St. Margaret of Cortona - incorrupt in Catholic parlance meaning partially or wholly preserved through means of a miracle, and not by embalming. St. Margaret, for whom the basilica is named, is partially preserved, but she is decidedly not wholly preserved. (Side note: I don’t generally take photographs of relics out of respect for those to whom they are holy. Hence, no photo.) According to the town of Cortona, she is the patron saint of the falsely accused, the homeless, the insane, the orphaned, the mentally ill, midwives, penitents, single mothers, reformed prostitutes, stepchildren, tramps and hobos - although I am not 100% sure what the difference is between tramps and hobos.

I take the back way down to the town center so that I can follow the stations of the cross that line the way, decorated in mosaics by the brilliant Italian futurist artist Gino Severini, who was born in Cortona.

(Along the way, I am put to shame by an extremely elderly couple making the climb to the basilica slowly, but without breaking a sweat. I feel like this is probably a sign that I need to slow down on the ricciarelli.)

Sadly, plexiglass has been installed to “protect” the mosaics, and most of it is absolutely filthy and covered with dirt, making it difficult to see all but a few.

Why, Cortona, why?

{San Gimignano}

The rain is falling so hard on the day that I visit San Gimignano that I can barely see the top of the town’s famous towers. There are fourteen towers in this small town today, but eight hundred years ago there were over seventy. Seventy-two in fact. The tallest tower was (and still is) the Torre Grossa, the combination bell tower/watchtower perched atop San Gimignano’s town hall. Most of the other towers, though, belonged to private residences. It wasn’t just San Gimignano - towns and cities all over Italy were filled with tower houses in the Middle Ages. Built by family patriarchs as a form of protection and fortification, they also served to boost the ego: look how big my tower is.

The rain continues in Arezzo, and and in Spoleto. Endless rain. The autumn leaves that were so beautiful weeks ago are now scattered on the ground, washing over cobblestones. The skies are angry, the trees grow barer every day, and the gold of the Italian fall is quickly being replaced by shades of grown and grey.

As the end of November turns into the beginning of December, shop windows start to fill with fairy lights, and Christmas ornaments, and abundant displays of candies and cookies and other brightly wrapped delights.

Cabbage and carrots and brocoli and squash line the grocer’s shelves - some so beautifully that if I had even a shred of artistic ability I would take out some paper and watercolors and try to capture the tableau on paper. As I don’t, a photograph will have to do.

November is wild board season in Tuscany and shops are filled with boar fillets, boar sausage, and boar salami. Taxidermied boars stand at shop entrances and hang on walls. Possibly they are there all year - to be honest I’m not sure. But part of me thinks that maybe they just come out in November.

One Sunday afternoon, on a visit to Florence with my sister, we stop at a bronze sculpture of a boar in front of the Mercato Nuovo. He is Il Porcellino, the piglet. Originally cast in bronze by the artist Pietro Tacca in 1634, the original sculpture is (like David) safely tucked away in one of Florence’s museums. This piglet is a repica, and his nose is worn down from centuries of tourists rubbing it in order to secure a return trip to Florence. We take turn dropping coins into his mouth, hoping that they will fall into the grate at his feet. If the coins fall into the grate, one is granted good luck. If it bounces away, bad luck…but at least you’ll get to keep your coin.

Luckily it’s pretty easy to get the coin into the grate. Good luck all around.

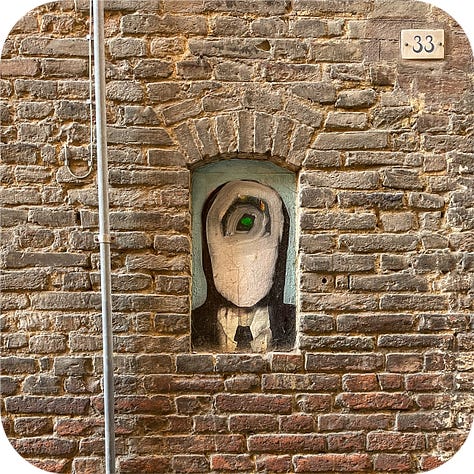

Back in Siena, a skull is set into the wall of Santa Maria della Scala. These days a museum, for a long time Santa Maria was a pilgrim’s hospital and orphanage. The skull has writing inscribed on his forehead, and above the nook in the wall that holds him, words painted in black.

Come tu sei fui ancor’io: com’io sono sarai ancor tu.

As you are, I was too: As I am, you will also be.

Their message is clear: memento mori. Remember you must die.

It’s downright cold now in Siena, but it’s also early evening - and the streets are crowded with locals, bundled up in scarves, and smiling as they walk.

It’s here in Tuscany that I learn about an Italian tradition: la passeggiata - the evening stroll. It’s a chance to see and be seen, to chat with neighbors. To acknowledge each other’s humanity.

It seems particularly important at this time of year.

I like this about Italy: the palpable weight of shared history, and shared humanity…and the acknowledgement of shared mortality. It’s not what I expected when I came here.

To be honest, I wonder if I’d feel this weight if I’d come in the spring, or in the summer - or if all my thoughts of humanity would simply melt away under the splendor of the famous Tuscan sun?

Maybe I’ll find out one day, who knows.

But for now, I’ll take my memories of Tuscany home with me just the way they are. I’ll take the memories, please, and maybe just a few more ricciarelli…

XO

PS - If you enjoyed this letter, please consider becoming a subscriber to have Beautiful Things delivered to your inbox. Subscriptions are free, unless you choose otherwise. If you are interested in reading my previous letters from abroad, visit my homepage: Beautiful Things. Finally, absolutely no pressure at all, but if you’d like to support my writing, I’ve added a virtual tip jar as well: you can find the “Buy me a coffee” button below. Thank you for reading!

Love to read you. Bravissima

"since I’ve arrived in Siena I’ve been eating ricciarelli like it’s my job." as always I am transported by your writing and align with the above with every ounce of my soul.